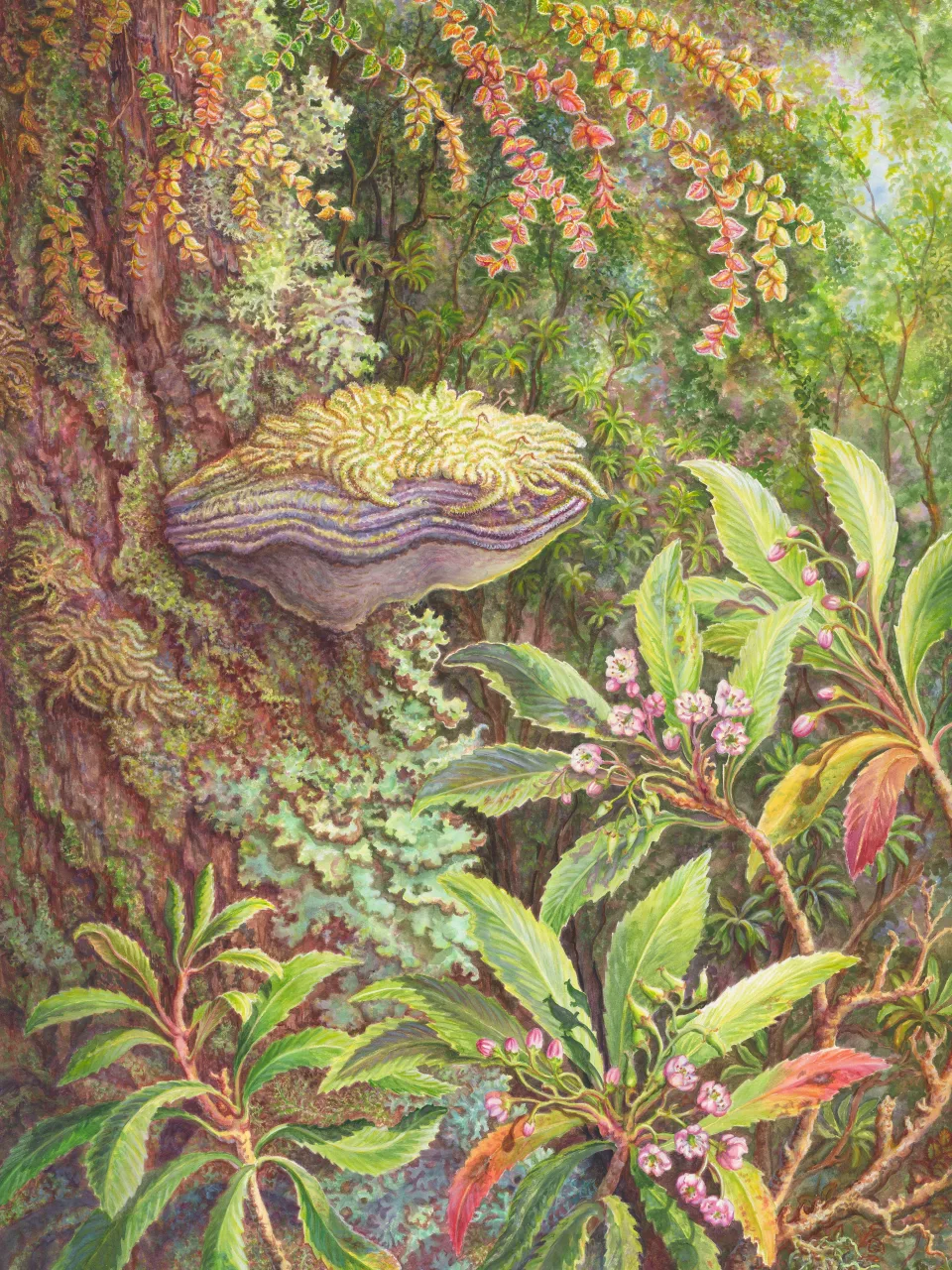

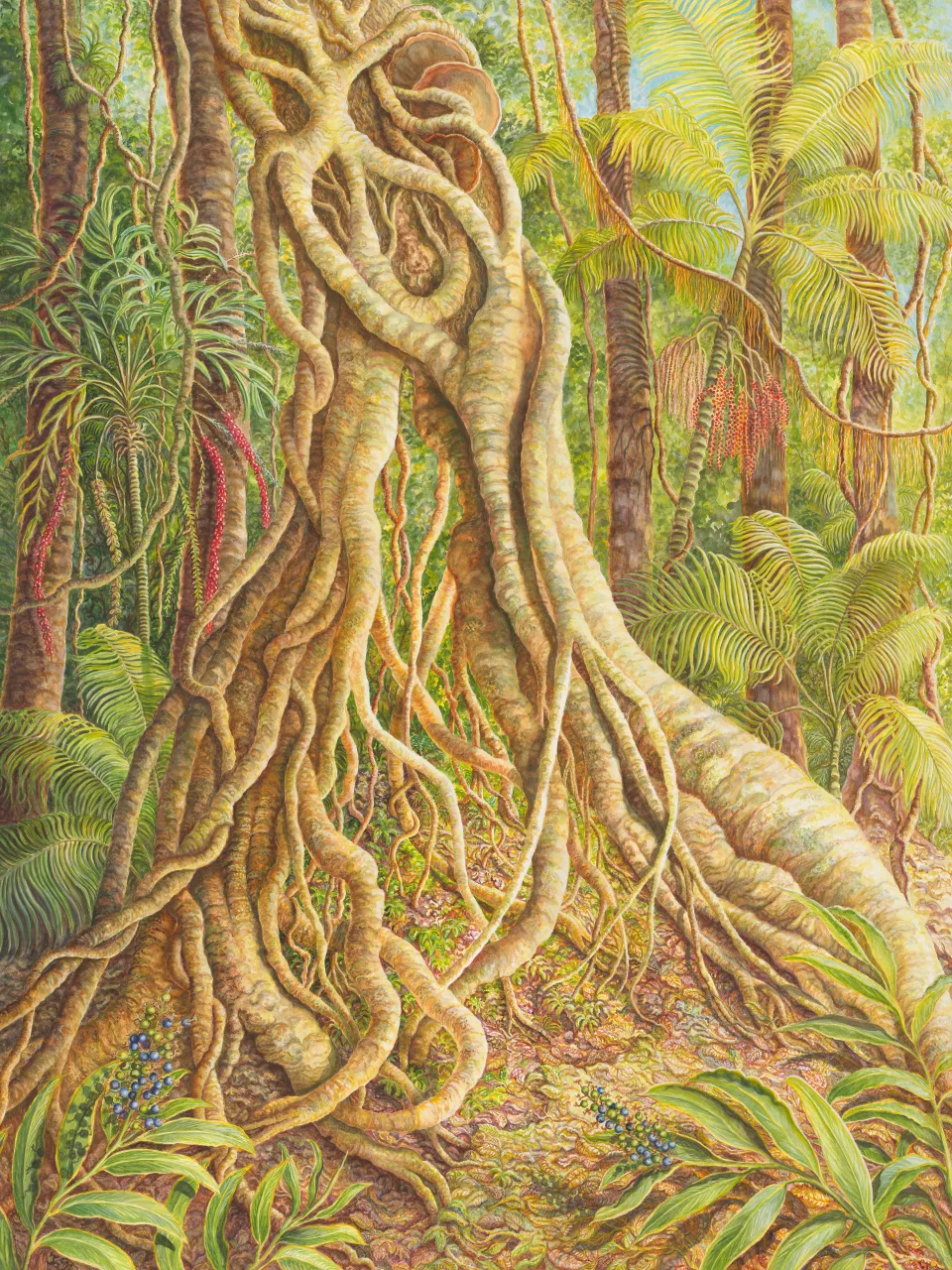

Artwork 3 Lyrical Lichens and Fluorescent Fungi

Section 4

Fungi, Mosses, and Lichens

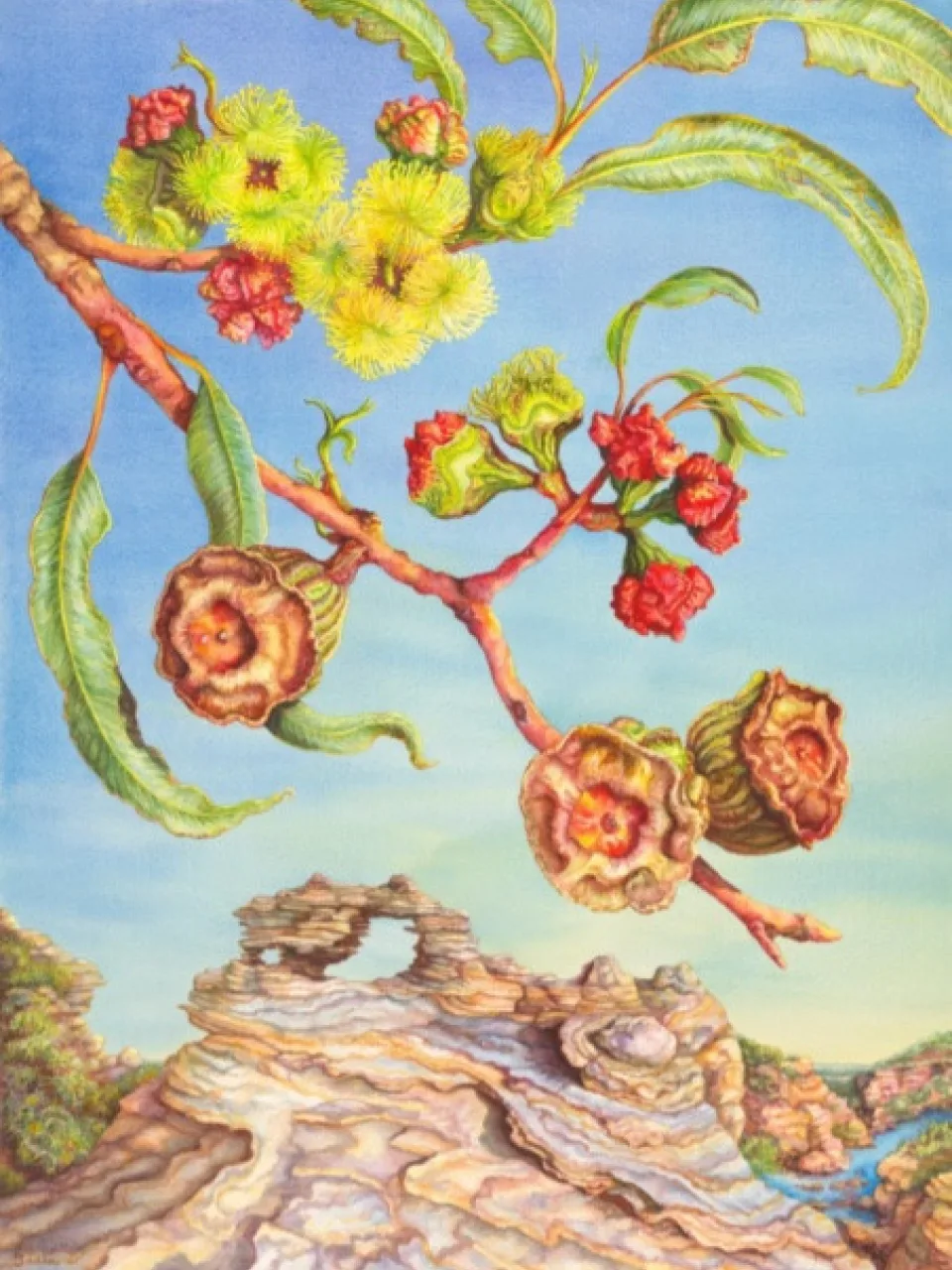

Southwest National Park, Tasmania, Western Australia

- 1. Hypolepis amaurorachis (austral ground ferns)

- 2. Nothofagus cunninghamii (southern beech)

- 3. Pseudocyphellaria billardierei (lichen)

- 4. Pseudocyphellaria rubella (lichen)

- 5. Trametes versicolor (rainbow fungi)

- 6. Weymouthia cochlearifolia (moss)

Artwork 3

Buy a print

Limited edition giclee archival quality print on 310 gsm Ilford cotton rag (from an original work in watermedia on watercolour board, 76 cm high x 51 cm wide)

from the artist

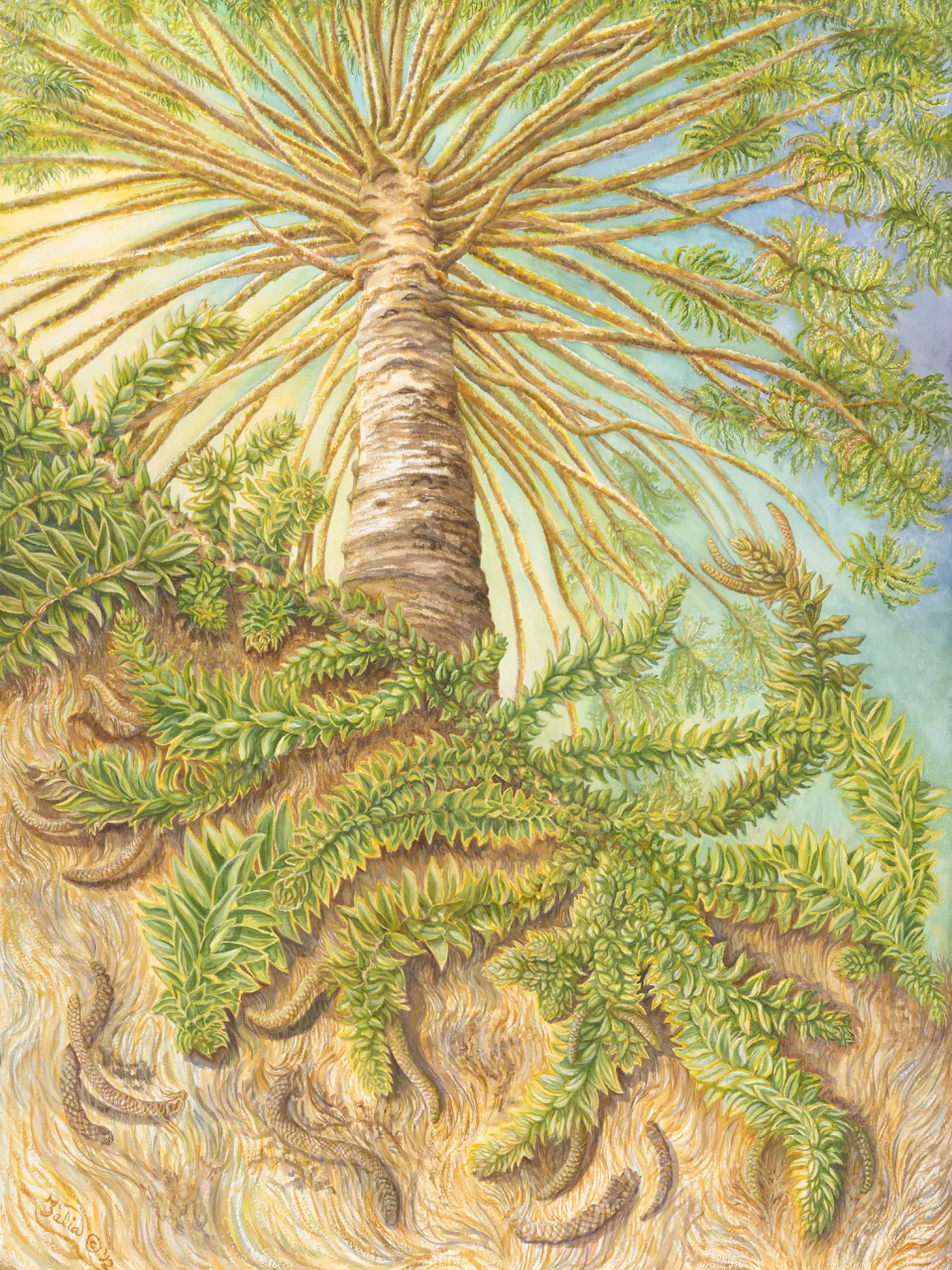

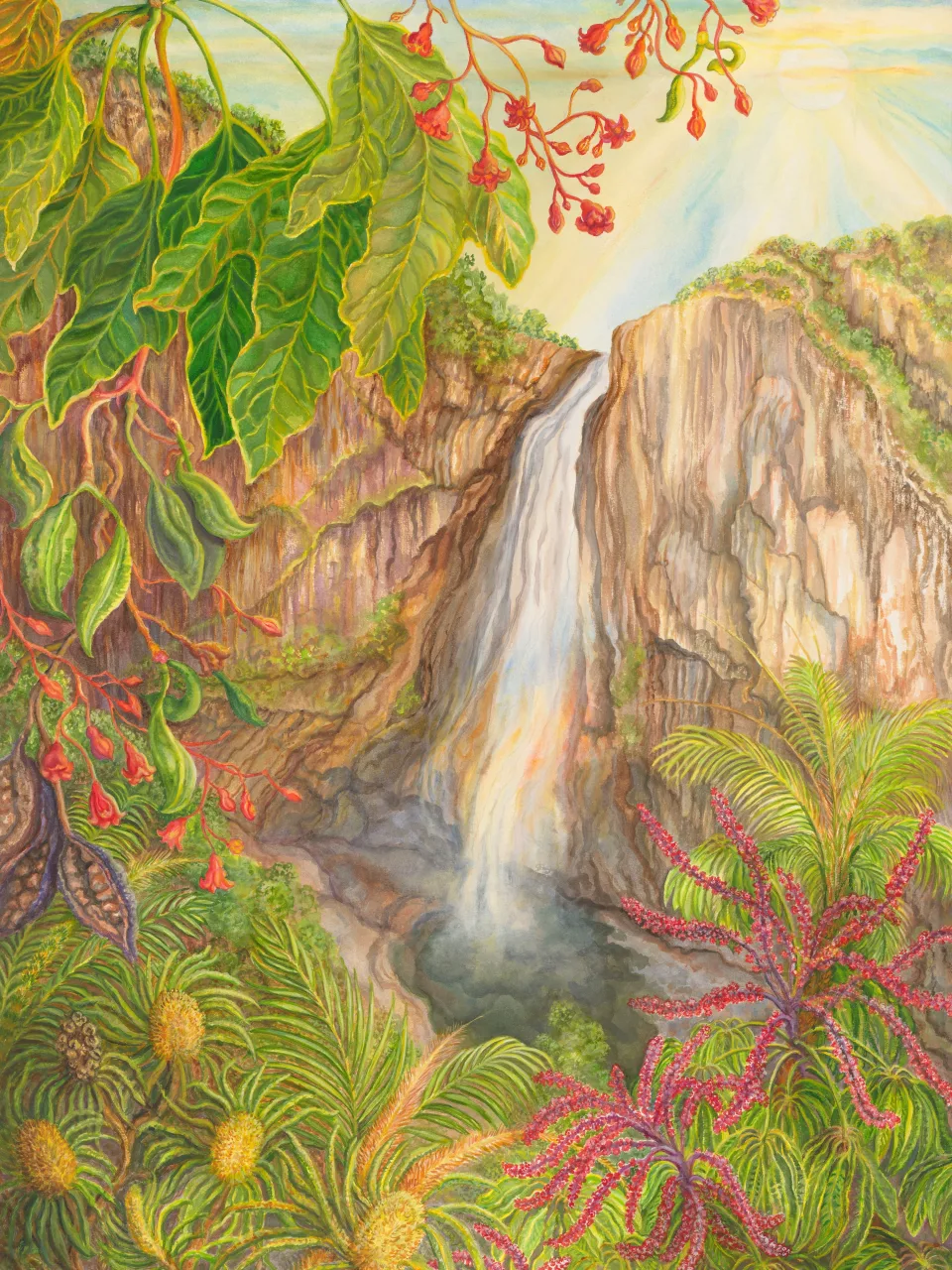

I chose the title for this painting after becoming fascinated by the great variety of colourful and intricately-patterned lichens thriving in the rainforests of south-western Tasmania. Many beautiful lichens were accompanied on living trees and fallen logs by a crowded mosaic of mosses and fungi. The “fluorescent fungi” featured in this artwork appeared to glow with shifting iridescent colours in the rapidly changing light, as rain clouds and showers alternated with flashes of filigreed sunlight. The layers of deep blue, purple, rust, and cream had an almost phosphorescent quality, especially in the half-light of dusk.

These colourful fungi are Trametes versicolor with an apt common name—rainbow fungi. They were growing on a dead upright tree trunk at the edge of the rainforest near Lake Pedder. Rainbow fungi commonly appear on dead branches, logs, and fence posts, and are active wood-decaying fungi, sometimes even parasitising living trees. Like other fungi such as mushrooms or toadstools, they do not contain chlorophyll, and cannot make their own food by photosynthesis.

Unlike their surface-living relatives, microscopic soil-forming fungi (mycorrhizal fungi) assist plant growth. They form successful symbiotic (mutually beneficial) relationships with the root systems of plants, and have done so for at least 400 million years.

Another symbiosis success story for fungi is the combination of algae and fungi to form a new type of plant life—lichens. The alga possesses chlorophyll, and so can photosynthesise to provide food for the fungus. The fungus, in turn, provides the body of the plant where the alga finds shelter amongst the fungal cells and threads. Lichens are ancient plants, and were probably amongst the very earliest to live on land when life moved out of the seas over 400 mya.

The brilliant yellow-green lichen in the central area of the painting has no common name. It is a foliose (“flat and leaf-like”) lichen called Pseudocyphellaria billardierei. I was fascinated to learn that Pseudocyphellaria species contain cyanobacteria— “cousins” to those still busily forming stromatolites today—in symbiotic partnership with fungi.

Resembling a smaller version of the surrounding rainforest itself, the dead upright tree trunk I painted seemed to be home to a wonderful variety of lichens, fungi, and mosses. Mosses are also ancient plants and grow in stunningly varied environments throughout the world. Most have an amazing ability to dry out, look quite dead, and then revive rapidly with the slightest sprinkle of moisture.